soziale stadt - bundestransferstelle

besonderem Entwicklungsbedarf - Soziale Stadt"

Hanover Vahrenheide-Ost |

|||||||

|

Heiko Geiling |

|||||||

Exceptionally, the model area Hanover-Vahrenheide Hanover-Vahrenheide is not a designated "Socially Integrative City" programme area. Vahrenheide-Ost had already been included in the Lower Saxony urban development programme under the "Integrated Renewal Vahrenheide-Ost" in 1997. Developed jointly by the Gesellschaft für Bauen und Wohnen Hanover mbH (GBH) and the Hanover municipality (planning authority), this regeneration concept allowed Vahrenheide-Ost to be taken as a model area for Lower Saxony because of its novel, integrative character. The reasons for urban renewal were not so much constructional and planning deficiencies as "problems arising from the disadvantaged situation of the local population" (Status Report 2000, p. 11).

In keeping with the state government's legal requirements, the model area covers only the officially designated action area. This restriction has been ignored here in favour of describing the entire Vahrenheide district in order to explain the actual interlinkages and use contexts.

1. Nature of the Area

Vahrenheide is situated on the northern boundaries of the Lower Saxony capital Hanover, some four kilometres as the crow flies from the centre of town. The district is well served by public transport in the form of a tram route. Vahrenheide is separated from surrounding districts by the Mittelland Canal to the south, a motorway to the north, and busy streets to the east and west.

The district was developed between 1955 and 1974 as the first Lower Saxony large-scale housing estate on the city periphery. The pure residential area is divided into three parts. Three or four-storey terrace buildings with a total of about 2,280 dwellings cover the greatest area. West Vahrenheide is dominated by an extensive area of single-family row houses, while only the south-eastern part of the district is characterised by concentrated high-rise development (about 600 dwellings) up to 18 storeys high. Since the development of the district was not completed to the extent planned, the Vahrenheide Market, which was intended to be the centre of the district, remains on the fringe of the residential area.

|

| View of south-eastern Vahrenheide, in the foreground terrace buildings from the 60s, in the background the high-rise complex of Klingenthal. (Source: Franz Fender) |

From the outset, Vahrenheide, with a large supply of publicly financed or subsidised housing stock, had the function of providing housing for people and families unable to meet the usual rental costs without assistance. Such public housing subject to occupancy rights is allocated by the housing office, and, since recently, directly by the municipal housing company GBH. Since the proportion of dwellings reserved for low-income tenants (87%) is almost twice as high as in comparable Hanover districts, a strong spatial concentration of socially disadvantaged milieus has resulted.

|

District boundaries showing the layout of the urban renewal area (Source: agis, Hanover) |

However it does not do justice to the specific situation to describe the area indiscriminately as deprived, although at least half the residents live below or close to the poverty line. For, despite these difficult personal circumstances, two-thirds of Vahrenheide residents make a living independently of government transfer payments. Some 20% live in relative material security (including home ownership), about 50% live in modest social conditions but are economically independent, and approximately 30% receive social assistance or unemployment benefits, of whom 8% are in a situation of extreme deprivation. Extreme deprivation, i.e., a life situation in which material difficulties and unemployment are exacerbated by psycho-social problems (addiction, occasional homelessness, social isolation, etc.) primarily affects German residents. Although people with a migrant background are almost twice as likely to receive transfer payments as Germans, there is a lower German substratum.

The specific age structure in the district contributes to the low earning potential. A higher than average proportion of children and young people live in Vahrenheide. In keeping with the overall societal trend, the proportion of senior citizens is also relatively high. As a result, only half the population are of employable age, of whom, in turn, a higher than average proportion are unemployed because the claims of child rearing preclude them from taking up gainful employment and they remain dependent on social assistance. The age structure is "rejuvenated" by the high percentage of migrants.

A differentiated analysis of fluctuation in the area records a longer period of residence for the Turkish population - by far the majority of migrants in the district - than for the population as a whole. In Vahrenheide-Ost 34% of the total population but 46% of the Turkish population had lived in the area for over 5 years (cf. Janßen 2001). Migrants tend to constitute the relatively stable population groups in the district.

2. Main Problems and Development Potential

The main problems in Vahrenheide are poverty and dependence on transfer payments. The situation is exacerbated by the strong spatial concentration of disadvantaged and ethnic milieus in the run-down GBH housing. In everyday life, this leads to strongly overburdened neighbourhoods, everyday cultural alienation and stigmatisation, making it difficult to live together in harmony.

Social cohesion is already rendered problematic by the structural monostructure of a purely residential area. In view of the purely welfare economy, there are scarcely any jobs or earning opportunities. Furthermore, everyday life is shaped by the imbalance between indoor space and outdoor areas. Not only is living space restricted, but many social facilities are also very cramped. There is a lack of opportunities for cross-milieu encounters in the form of venues and structures that permit contact and socialising. In particular, there is a lack of day-centres for toddlers and for school-children, of possibilities for getting together, and of local employment and qualification facilities. Health care services are minimal, and there are hardly any public places where the many ethnic groups (58 different nationalities) can live their everyday culture. In addition, there is Vahrenheide's negative image, both external and internal, which makes it more difficult for residents to identify with the district.

Demography and Social Space

|

Vahrenheide-Ost (1) |

Vahrenheide District |

Hanover |

|

|

Size |

73 ha |

139.8 ha |

20 407 ha |

|

Population (2001) |

7 535 |

9 319 |

505 648 |

|

Population decline (1995–2000) |

9.9 % |

9.3 % |

1.8 % |

|

Average household size |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Number of dwellings (1999) |

3 300 |

4 662 |

281 787 |

|

Vacancy rate (2000) |

10.9 % (2) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Housing benefit recipients (1995) |

13.6 % |

10.6 % |

5.7 % |

|

Unemployment rate (2001) |

20.3 % |

18.6 % |

10.1 % |

|

Social assistance recipients (2001) |

20.7 % |

17.6 % |

7.3 % |

|

Foreign population (2001) |

33.9 % |

30.9 % |

15.0 % |

|

Population under 18 (2001) |

23.4 % |

21.5 % |

15.3 % |

|

Population 65 and older (2001) |

24.3 % |

26.1 % |

25.0 % |

|

(1) The urban renewal area covers the eastern part of the district, with the exception of three single-family house areas and some privately owned apartment blocks to the north. |

|||

Only a small section of the district population is politically represented; e.g., at the Bundestag election in 1998, only 57% of residents were entitled to vote. 73% exercised their right to vote, but in the narrower action area, only 66%. Less than half (41%) thus influenced the political representation of the area.

Important potential for development, which could in the long run counteract the trend towards impoverishment, lies in early childhood care and school education. Because of the dimensions of this long-standing problem, the central day nurseries, like the Vahrenheide-Sahlkamp integrated comprehensive school and the secondary grammar school are all-day facilities. These institutions put novel and committed concepts into practice that take account of the specific needs of children and young people (e.g., for exercise and reliable significant persons). In spite of the additional pedagogic and care functions they assume, the cramped conditions and poor equipment, the schools do a sound educational job.

|

Partial view of the Vahrenheide Market with a "Cultural Centre" advertising pillar and sandstone stelae from a Culture Centre creativity campaign. (Source: agis, Hanover) |

Social cohesion is also supported by many of the social institutions in Vahrenheide. They include Neighbourhood Initiative, Play Park, and Community Work, which have had many years of experience in integrating underprivileged groups and migrants. If the traditional sports clubs and cultural associations could be made sufficiently aware of the problem and more open to the way of life of younger people in the district, they could help bridge existing gaps. The migrant associations based on ethnic ties (e.g., the Democratic Cultural Association) have already established neighbourhood networks.

Given its key position in the district, the municipal housing company GBH can also offer potential for developing the area. A GBH office has meanwhile been set up locally, which has brought day-to-day work closer to residents. Furthermore, the housing company has for some years been more intensively promoting and financing social work and employment projects.

3. Development Goals and Focal Points of Action

The objective of renewal in Vahrenheide-Ost is the social stabilisation of the district and the improvement of living conditions for its residents (see housing policy guidelines). This goal is to be attained by improving opportunities for earning, for exerting influence, and for gaining experience. These objectives are defined in the "Integrated Renewal Programme Vahrenheide-Ost" (1997). Five focal points of action have been identified and concretised to varying extents.

In Hanover, local "housing policy" is closely linked with a city-wide concept for combating increasing social-space segregation ("Action Programme Living in Hanover"). In Vahrenheide, priority has been given to correcting the imbalance in the composition of the residential population (social deconcentration) and developing workable neighbourhoods. This is to be achieved by making housing available for other social milieus. Specifically, occupancy rights are to be suspended for a limited period for about 70% of GBH dwellings, and the allocation of housing delegated to the district GBH office (formerly the responsibility of the housing office). In 1999 allocation restrictions were lifted on some 800 dwellings, especially in the tower blocks, and in 2001 on another 1000 or so (Article 7 of the Act on Housing Occupancy Rights). Another instrument is privatisation: in 2000, 36 high-rise housing units were sold to a new cooperative housing association (VASA), and a further 42 units from the 1960s housing stock were sold in 2001. 136 dwellings in an up to 9-storey terrace building are also to be sold to tenants or owner-occupiers.

The main focus is on rehabilitation, especially improving particularly dilapidated housing elements and business centres. The vast majority of available funding is earmarked for this purpose. The superordinate goal is a greater mix of dwelling and working uses. It is hoped to achieve this by converting existing dwellings for social and commercial purposes and residents' institutions, and by establishing non-disturbing industry. It is also hoped that remodelling will encourage residents to take advantage of the residential environment. The considerable work input for these remedial measures is to give residents at least temporary employment and opportunities for initial and continuing training.

In the "social and cultural infrastructure" field, existing and to some extent overburdened services are to be stabilised and supplemented. An important target group are children and adolescents, for whom additional "meeting situations" as well as educational and qualification opportunities are to be provided. Cross-milieu activities are to be improved by, for example, the relocation and expansion of an existing cultural centre. A round table to which all social and cultural facilities, institutions, and civic groups active in the district were invited, discussed what action needed to be taken, which was also the subject of a survey. Cooperation is planned to develop a social action programme.

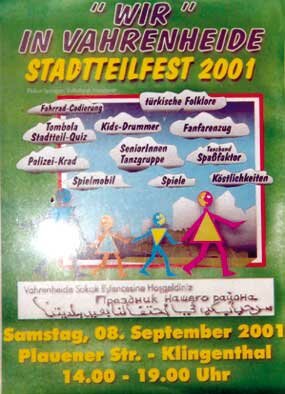

|

Poster advertising the 2001 district festival (Source: agis, Hanover) |

In the field of "participation and activation for personal initiative and self-organisation," the central revitalisation goals can be attained only through greater social and political engagement on the part of residents. This is to be achieved at three levels of action: intensive public relations work is to inform residents about renewal projects, opportunities for participation and action; possibilities for participating in local planning and decision-making processes are to be established and strengthened, and neighbourhood communication, self-help and self-organisation are to be promoted as the most important element.

The objective in the "local economy" area is to create temporary and permanent employment opportunities in the district itself. Three key factors come into play in implementing this difficult task in a purely residential area: the adjoining industrial area, the two business centres, and the housing company GBH as the biggest landlord and investor in the district.

The extensive investment in housing stock and the residential environment, in particular, is to be used to provide work and training opportunities in the district. The establishment of a local employment enterprise is intended to supplement and coordinate activities in the area of action and to promote informal approaches to self-help and neighbourhood support.

|

Emmy Lanzke House day nursery run by the AWO: there are long waiting lists for day centres and kindergartens. (Source: agis, Hanover) |

4. Key Projects

The "Status Report September 2001" listed 35 different projects and measures for citizen participation that have been developed since the start of actual work in the programme area (summer 1999). The radius of action, term, and cost of the projects and measures vary considerably. The projects dealt with in detail are those that are of central importance because of their strategic status in achieving the revitalisation goals and because of the extent of funding.

|

| View of part of the Klingenthal high-rise complex, which is to be partially demolished in the course of rehabilitation (Source: Sanierungszeitung Nr. 15, 7. 6. 2001) |

- Housing policy control (lifting of occupancy rights, limited exemption from allocation control, privatisation of housing) is hoped to have a crucial impact on the district and its social structures. These measures to open up local housing to other groups of residents have (so far) had little effect.

- Because of its high symbolic and social importance for the entire district, the DM 13 million "Redevelopment of the Klingethal Estate" plays a key role. In the core area of the more than half empty high-rise complex (560 dwellings) 226 units are to be demolished. Proposals for redesign which had already been obtained could not be realised because the housing company lacked the financial means and no other funding was available (the dwellings have been modernised), although some tenants had clearly expressed their opposition to demolition. A social compensation plan is currently being developed with the remaining tenants, under which they are guaranteed the right to stay in the model area (if they so desire). Since the high-rise complex is subject to stigmatisation, which extends to the entire district, and demolition means a highly visible change in the image of the district, this measure should have a positive knock-on effect.

- The urgently needed modernisation and rehabilitation of the GBH's 1960s housing stock requires about DM 14.5 million. The measures are being coordinated with GBHJ tenant associations, and residents are involved in specific implementation.

|

Rehabilitated façade of 1960s housing, typical GBH mid-rise development. (Source: agis, Hanover) |

- Another important project is "Supervised Housing in the Sahlkamp Buildings," which aims to support and activate extremely disadvantaged residents. These buildings and their mostly very small dwelling units have the worst image in the district and are in great need of repair and modernisation. Most tenants are single men with a wide range of social problems and frequent interpersonal conflicts. On behalf of the urban renewal commission, the urban renewal office has developed a concept for social care in cooperation with the municipal social services, Community Work, the housing office, and an external expert. Residents are offered advice and counselling to foster social stabilisation. To some extent assistance is given towards vocational rehabilitation and in finding employment.

- A key project that covers several areas of action is the establishment of a self-organised residents' centre in the present Home for Single Mothers. Together with the Neighbourhood Initiative, the most important local residents' organisation in the district, the newly founded association for employment promotion "FLAIS" and the Workers' Welfare Organisation (AWO), the urban renewal office initiated the elaboration of a use concept. The cost of structural conversion can be meet from rehabilitation funds. The financing of the operation of such a centre is currently controversial.

|

New caretaker's lodge in a tower block of the Klingenthal complex intended to enhance the attractiveness of the entrance area and residents' sense of security. (Source: agis, Hanover) |

5. Organisation and Management

This novel, integrated rehabilitation plan for Vahrenheide-Ost is based organisationally on 30 years of cooperation between the Hanover municipality (local planning authority) which has overall responsibility for urban renewal, and the municipal building and housing company Gesellschaft für Bauen und Wohnen (GBH). In Vahrenheide urban renewal has always been primarily district improvement funded by housing construction and urban development promotion schemes. Two tried and tested instruments have emerged from this tradition of urban renewal.

- An urban renewal commission has been set up to act as a local decision-making body. It is composed of six elected representatives of political parties (in parity with the city council) and six representatives of the public selected by the commission. The commission can coordinate important clarification and decision-making processes locally, relieving the city council - which has the last say - of detailed local work. As a rule, the city council follows the proposals submitted by the commission. der Regel folgt der Rat der Stadt den ausgearbeiteten Vorlagen der Sanierungskommission.

- Residents are supported in all planning and participatory procedures by advocacy planning. This concept, which originates from the United States, helps get a fair hearing for actors that carry little clout and for neglected issues, but also mediates between actors in an informative, interlinking, networking, moderating, translating, and participatory capacity.

New forms of organisation and management were, however, required for the first-time regeneration of a "deprived area" under an integrated action programme.

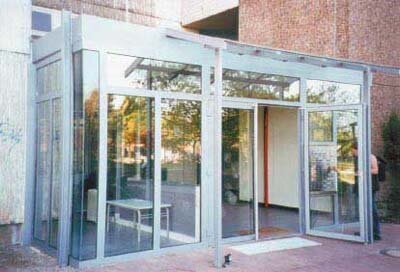

|

The urban renewal office has its premises on the lower floor of a converted parking building dating from the early 1990s. On the floor above are the offices of Community Action and a branch of the housing company GBH. (Source: agis, Hanover) |

|

Founding meeting of the citizens' forum in June 1998 (Source: Thomas Oberdorfer, Hanover) |

- The process is controlled by a specifically constituted district renewal office located in the area. The building department has overall control of the entire regeneration process and is locally represented by an urban planner. The latter collaborates closely within the administration with a social planner and with a urban renewal coordinator, who is, however, also responsible for other areas. An architect acts as the redevelopment agent of the housing company GBH. Given the goal of social stabilisation, a community worker previously employed in the district was also appointed urban renewal commissioner for the welfare department. Work in the urban renewal office is coordinated by an independent, experienced urban renewal commissioner. He acts in a mediating and activating capacity in relation to the various networks (district actors, local politics, administrative authorities, GBH, municipal politics). Work focuses on providing information and support for residents, coordinating and moderating the projects of all relevant actors in the district, and developing (integrated) projects.

- The urban renewal office has initiated a citizens' forum as the central participatory body for residents. It is intended to broaden the far too narrow basis for active political participation and local self-organisation (residents, associations, civic groups) and bundle the activities of existing actors. The citizens' forum initially met every two weeks, now every four weeks, and is chaired by a resident. All remedial measures planned are presented at the forum before they are discussed and adopted by the urban renewal commission. The citizens' forum also has the de facto right to decide on the allocation of money from the district fund to the amount of DM 50,000 annually.

|

Currently participating actors in "Integrated Renewal Vahrenheide-Ost" and the "Socially Integrative City" programme |

New at the municipality level are the "Socially Integrative City" steering group and coordinating group. The steering group is composed by the competent heads of administrative units, who also make the central decisions and determine the general framework. The coordination group is the organisational heart of the "Socially Integrative City" programme, and is presided over by a member of the municipal planning authority. This group is the interface between the competent municipal authority staff and the people operating at the local level. They are responsible for preparing and carrying out measures, coordinating cross-area projects, exchanging information, discussing concepts, and solving problems without undue red tape. The new, cross-authority "circles" cut across the vertical divisions between administrative units while leaving the decision-making hierarchy intact.

Most important for the rehabilitation process are new on-the-spot organisations. the urban renewal commission and office, the citizens' forum, and advocacy planning. Links with residents, their interests and demands are to be achieved primarily by the citizens' forum with the support of advocacy planning. So far there is no body bringing together the individual organisations in the district.

6. |

Activation and Participation of Neighbourhood Residents/District Actors

|

Vahrenheide was chosen as an urban renewal area and model district because of the higher than average proportion of residents in difficult personal circumstances (poverty, unemployment, immigration, large families) concentrated in the district. No sustainable change for the better in their social situation is conceivable without greater participation. Improving the position of disadvantaged residents vis-à-vis professional actors from the municipal authorities, the housing industry, and the social services to such an extent that participation becomes possible is a difficult and lengthy learning process. The legal procedures as well as many instruments for citizen participation favour educated, well organised, and assertive residents or resident groups and local actors. To avoid marginalising the interests of socially disadvantaged residents, activation and participation techniques specially adapted to these milieus are needed.

Since the 1980s, activation methods like outreach district social work (churches, community action, municipal social services, streetwork), networking meetings, and targeted services (public youth or resident centres) have been increasingly applied in Vahrenheide. In planning and neighbourhood improvement (e.g., the project "project "Green Messages") residents have become involved especially when, being directly affected, they were reached by a flyer in the mailbox or a ring at the door, when meetings were held in the building or directly in front of it, and tangible or visible proposals were put forward. Since the beginning of renewal work, these low-threshold activation techniques have been used especially in the case of dwelling modernisation and residential environment improvement projects.

The start of district renewal was marked by a district conference, initiated and staged by the main actors. It was followed by the opening of an urban renewal office in the district, and the newly appointed urban renewal commission met. Residents or interest groups who have comments to make or questions to ask about the work of the commission nevertheless have to submit to formalised rules of procedure and agendas.

It soon became apparent that, owing to the lack of active members, the new citizens' forum was overburdened by the substantive and organisational work such a body entails. Much of the necessary preparatory work was then assumed by the urban renewal office. What the office could not take over was the necessary advocacy planning function for the citizens' forum. As usual, participation in the citizens' forum was strongly selective from a social point of view. Neither the various migrant groups nor deprived German milieus or younger residents were adequately represented. Those responsible expected greater commitment in the citizens' forum from a planned increase in the neighbourhood fund, where the forum has a say in allocation. To improve the situation, the following participatory measures are being employed or planned:

- Housing company (GBH) tenant associations have been given greater attention and are supported by the urban renewal office.

- Active residents and active members of local institutions are currently being chosen as participation multipliers and being trained for this activity. A comprehensive "Guide to Vahrenheide" has been developed - not only for this work - which summarises all cultural, leisure, and advisory services in the district and provides information on contacts and opportunities for participation.

- The "Democratic Cultural Association," which represents the largest and so far comparatively inactive ethnic group in the district, the Turks, supports and promotes the integration of migrants.

- The urban renewal office intensified the promotion of self-organisation, especially in the form of residents' associations. This important area is to be supported by an office for employment and local economy, and will in future be given greater emphasis.

Information and public relations work is organised and financed by the Hanover municipality as the authority in overall charge together with the urban renewal office and the journalists engaged for the purpose. All households receive the twice-monthly newspaper "Sanierungszeitung Vahrenheide-Ost." It provides information on the main revitalisation activities, dates and events, and on the activities of residents, civic groups, and local institutions. Like the "Sanierungszeitung," flyers and posters appear in German with summaries in Turkish and Russian.

7. Conclusion: Upgrading and "Deconcentration" through Demolition?

The regeneration of the Vahrenheide district is based on a demanding, integrated concept. Despite a wide range of activities and committed projects at the local level, it must be admitted that the goals set, e.g., to correct the imbalance in the composition of the resident population through "deconcentration measures," can be attained only in the long term. Privatisation of housing has been achieved to any substantial extent only in communal form, by the sale of individual buildings to a district cooperative (VASA). Privatisation by sale to owner-occupiers or tenants has proved difficult. This means the money is lacking for acquiring occupancy rights in other districts, an important precondition for "deconcentration."

It is now apparent that the money available for renewal work - DM 30 million - will not suffice, given decades of inadequate investment and the specific problems Vahrenheide faces. In the past, some DM 200 million were spent in Hanover on district renewal. The funds now available for Vahrenheide suffice only to remedy the most serious shortcomings. Improving housing, let alone the district as a whole, for "other groups of residents" is hardly a realistic goal in this framework, especially since the demolition of sections of the high-rise complex tie up a considerable proportion of available funds and limit the housing company's capacity to invest.

The many years of experience and commitment, especially for disadvantaged sections of the population, have been bundled and developed since the beginning of regeneration work, particularly for new projects in the field of employment and qualification. This area is to be upgraded with a planned office for employment and local economy. Social stabilisation is also fostered by several self-organised resident associations supported or initiated by the district renewal project. What has proved problematic for these important activities is that the limited term of support does not permit a continuing perspective. This is also the case for the key project of a self-organised residents' centre.

To permit effective cooperation between politics, administration, the housing industry, local institutions, and residents, (in the sense of co-producers), differences in mentality, time rhythms, assertiveness, and priorities must be taken more strongly into account. In addition, conciliatory, independent moderation and more effective support from residents is needed. Cooperation in Vahrenheide suffers from the separate functioning of the bodies that represent interests and make decisions: The urban renewal commission (local politics), the citizens' forum (residents), the housing industry, the urban renewal office (administration, housing industry, independent urban renewal commissioner), the coordination group (professionals from local institutions). Because of this situation, the Hanover programme support team has proposed an overarching district forum. A district conference is to discuss the reorganisation of local bodies in the spring.

References

![]() Aktionsprogramm integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost (= Landeshauptstadt Hanover/GBH Bauen + Wohnen, Aktionsprogramm integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost - Ansätze für eine soziale Stadterneuerungspolitik, Hannover 1997).

Aktionsprogramm integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost (= Landeshauptstadt Hanover/GBH Bauen + Wohnen, Aktionsprogramm integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost - Ansätze für eine soziale Stadterneuerungspolitik, Hannover 1997).

![]() Aktionsprogramm Wohnen in Hanover (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Beschlussdrucksache Nr. 2569/99).

Aktionsprogramm Wohnen in Hanover (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Beschlussdrucksache Nr. 2569/99).

![]() Janßen, Andrea, Segregation der türkischen Bevölkerung in Deutschland am Beispiel der Stadt Hanover, unpublished. Diploma dissertation, University of Oldenburg, 2001.

Janßen, Andrea, Segregation der türkischen Bevölkerung in Deutschland am Beispiel der Stadt Hanover, unpublished. Diploma dissertation, University of Oldenburg, 2001.

![]() Leitfaden Vahrenheide (= AG Leitfaden (eds..): Leitfaden Vahrenheide. Kultur, Freizeit, Beratung im Überblick, Hannover 2001).

Leitfaden Vahrenheide (= AG Leitfaden (eds..): Leitfaden Vahrenheide. Kultur, Freizeit, Beratung im Überblick, Hannover 2001).

![]() Sachbericht September 2001 (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Stadtplanungsamt (ed.), Sachbericht: Integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost, September 2001).

Sachbericht September 2001 (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Stadtplanungsamt (ed.), Sachbericht: Integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost, September 2001).

![]() Sachstandsbericht 2000 (= Sanierungsbüro Vahrenheide-Ost (Hrsg.), Integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost, Sachstandsbericht Mai 2000, Hanover 2000).

Sachstandsbericht 2000 (= Sanierungsbüro Vahrenheide-Ost (Hrsg.), Integrierte Sanierung Vahrenheide-Ost, Sachstandsbericht Mai 2000, Hanover 2000).

![]() Wohnungspolitische Leitlinien (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Beschlussdrucksache Nr. 2345/98. Wohnungspolitische Leitlinien. Sanierungsgebiet Vahrenheide-Ost).

Wohnungspolitische Leitlinien (= Landeshauptstadt Hannover, Beschlussdrucksache Nr. 2345/98. Wohnungspolitische Leitlinien. Sanierungsgebiet Vahrenheide-Ost).

Im Auftrag des BMVBS vertreten durch das BBR. Zuletzt geändert am 25.05.2005